Photographic Materials

Many of the collections we process include photographic materials. Photographs have historically been the most requested items in NYPL reading rooms, and should be arranged and handled in a manner that can accommodate this high research demand. This section explains how to handle photographic materials you may encounter during processing. Most recommendations are from the University of California’s Guidelines for Efficient Processing. We also suggest consulting the Library of Congress’ Photographs and Prints Division website, Image Permanence Institute, and the SAA book Photographs: Archival Care and Management. A copy of this book is available in the conference room reference library.

Photographic materials that are located within the folders of other types of materials should generally not be physically separated. The photographs should be described within their existing context, and their locations can be noted in the finding aid’s container list and/or scope and content note. A form and genre term subject heading should also be added, which will notify researchers searching the catalog, as well as users scanning the finding aid’s front matter, that the collection includes photographic material. For more information on writing archival description, refer to the Archival Description section of this documentation. For more information about choosing accurate subject terms, see the Controlled Access Terms section of this documentation.

Photographic Prints

The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art (AAA) provides extensive guidelines on the preservation of photographic materials. Below are guidelines adapted from the AAA manual for the most common photographic materials that the NYPL houses.

To adhere to efficient processing, it is recommended to interleave personal photographs dating before 1950. Additionally, photographs that are deteriorated (such as early color photographs), damaged, fragile, or particularly significant should also be interleaved. Photographs that are included in folders of mixed material should always be interleaved to protect them from highly acidic documents such as newspapers.

Small photographs (smaller than 4”x5”) should be interleaved or placed in a larger paper envelope, to prevent getting lost among larger papers or photographs.

Existing Enclosures

Photographs should always be removed from glassine, brown paper envelopes, or envelopes from photo-processing companies. It is recommended that photographs be removed from non-archival plastic binder storage pages, especially if the plastic has become brittle, discolored, sticky, or deteriorated.

Photographs may be stored in paper envelopes, polyester/Mylar sleeves, or acid-free archival polypropylene sheets. Every single photograph in a collection does not need to be housed inside a Mylar sleeve or an envelope (unless they were already housed in that manner). However, some collections will require special housing considerations and your supervisor will communicate this to you if necessary.

Cased Photographs

Before developing a stable paper-based printing technique, many photographic processes utilized metal or glass as a base for images. These were then often placed behind glass, in a hinged, decorative case. However, both the enclosures and photographs themselves look extremely similar. Identification of these photographs takes some effort, and will be described below. However, the handling and storage of these objects are the same. Cased photographs should always be stored with the front cover closed. Wrap the enclosure with buffed tissue. Cased photographs come in a variety of sizes, and range from a whole plate (6½” × 8½”) to a “gem” (1 ½” x 1 ½”). If your collection has several cased photographs, try to find a box where they fit securely. If there is any extra space, add buffed tissue so the photographs do not move inside the box. Occasionally, you will find a photograph that is not in a case, rehouse these items like you would glass plate negatives or magic lantern slides, which is explained below.

Daguerreotypes: 1839 – 1860s, Glass plate with silver emulsion. Can be identified by a mirror-like surface. When placed on a dark background, the image appears to be a positive image, as the clear glass lets the color show through, the silver remaining on the plate reflects light to appear to be the lighter tones of the picture.

Ambrotypes: 1854 – 1880s, Glass plate was coated with collodion and dipped in silver nitrate. Ambrotypes have a less mirror-like surface than the daguerreotype. Like the daguerreotype, this plate is housed with a dark background, but when viewed from different angles, the image appears in both the positive and negative.

The ambrotype to the right illustrates a slightly damaged image, where the emulsion behind glass has been scratched, revealing the clear parts of the glass plate base.

Tintypes: 1853 – 1930s, Positive photograph on a thin sheet of metal, but often encased behind glass. When looking at a tintype at different angles, the image only appears in the positive.

The tintype to the right without a glass frame, when looked at from an angle the emulsion on top of the metal sheet can be seen.

Photograph Albums

Preservation decisions for photograph albums vary greatly depending on the condition of the album, and whether it is a bound volume or 3-ring binder of sleeves. The archivist, along with their supervisor, and in possible consultation with Conservation, will have to determine the level of preservation necessary for bound photograph volumes. When minimally processing a collection, do not take the time to interleave or dismantle bound albums unless they are especially significant, vintage, or damaged. Binders of photographs should always be dismantled and the sleeves placed in folders.

Slides

Slides should be stored in archival plastic slide pages. For efficient processing, only transfer slides to archival slide pages if the existing plastic pages have become brittle, discolored, sticky, or obviously deteriorating. Loose slides or slides stored in slide boxes should always be rehoused in plastic slide sleeves. Each slide should be placed in sleeves “emulsion side down.” This can be identified as the less shiny side of the negative in the slide case.

Negatives

Film-based negatives found within archival collections are cellulose nitrate, cellulose acetate, or polyester. To identify these three types, please refer to the Image Permanence Institute online guide.

Negatives should always be removed from glassine, brown paper envelopes, or envelopes from photo-processing companies.

Nitrate and Acetate Negatives

Nitrate and acetate negatives are unstable formats and will continue to deteriorate unless they are in cold/frozen storage conditions. When conducting a survey of a collection, if you find nitrate negatives or acetate negatives displaying vinegar syndrome, notify your supervisor immediately. Extensive exposure to degrading film can be hazardous to your health. Wear gloves and work in a well-ventilated area if you need to handle this material. If the decision is made to keep nitrate negatives or acetate negatives showing signs of vinegar syndrome, they should always be stored in separate containers from other collection material.

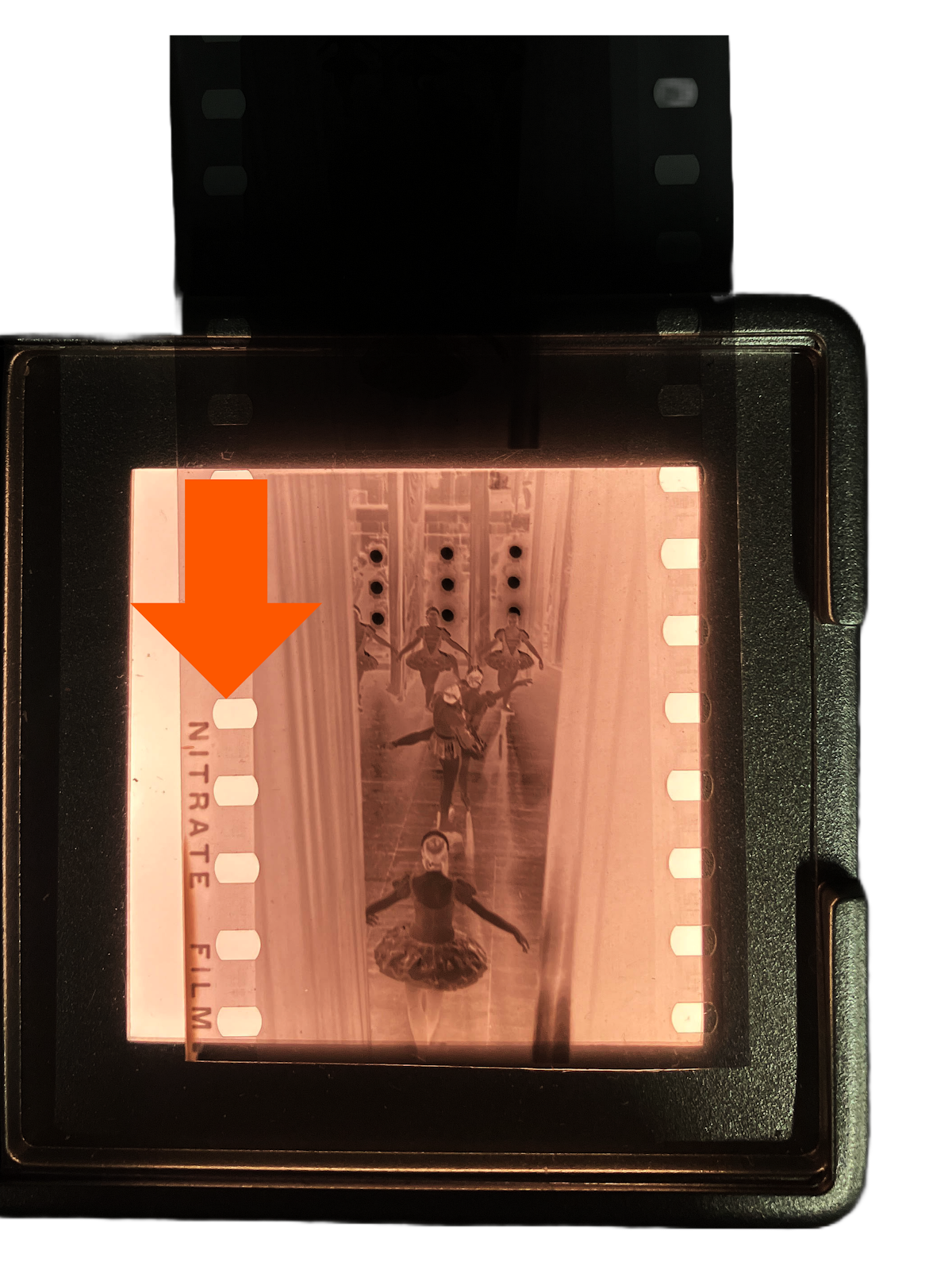

Nitrate Negatives

Nitrate negatives were produced from 1889 until the late 1950s. They are very similar in appearance to standard flexible non-nitrate black-and-white negatives. There are several ways to identify what type of negative you are handling. Most professional manufacturers print on the edge of the film “nitrate” or “safety” (non-nitrate) film.

Acetate Negatives

Acetate negatives that are not showing signs of vinegar syndrome may be stored in a box containing other material; however they should be placed in a separate folder because they will continue to deteriorate.Acetate negatives are a bit harder to identify visually, as they were still identified as “safety” by manufacturers. However, deteriorating negatives emit a powerful odor, and this deterioration is often called “vinegar syndrome,” as the base will have an extremely strong vinegar-like smell. If handling film, and you are unsure of the base and level of deterioration, there is also a test, where negatives can be placed in an air-tight container with an acid-detecting strip. This strip will then change color depending on the level of acid present.

Polyester Negatives

Polyester negatives are a very stable format and can be stored with other photographic or mixed material. It is still recommended that negatives be placed in a negative envelope or sleeve to separate it from other items in a folder. They can be interleaved as a group and not each individually. When storing negatives in plastic sleeves, they should be inserted emulsion-side down, the emulsion side is often identified as being less shiny and on rolled negatives, on the inner side of the curl.

Glass Plate Negatives

Glass plate negatives should be stored in a negative storage box appropriate for their size. Each glass plate should be placed in a paper envelope with the emulsion side facing away from the envelope adhesive. On glass plates and lantern slides, the emulsion is placed directly on the glass, and will appear to be right on the surface of the base. The non-emulsion side of the image appears to be behind glass. Odd sized glass plates should be placed in an envelope for the next size up, or in a handmade four-flap enclosure. If removing glass plates from old enclosures (small boxes, folders, or envelopes), transcribe any descriptive information onto the new negative envelope.

Lantern Slides

Lantern slides are typically a smaller format than glass plate negatives. They are usually color images (transparencies) placed within two pieces of glass and masked with tape on the edges. If a collection has large quantities, appropriate sized boxes (similar to Hollinger brand slide boxes) and four-flap enclosures can be utilized.